Page 12 Page 13

OPERATION

speed and is taking very small bites to produce tiny, cleanly-

severed chips. If the trimmer is forced to move forward too

fast, the speed of the cutter becomes slower than normal in

relation to its forward movement. As a result, the cutter must

take bigger bites as it revolves. Bigger bites mean bigger

chips and a rougher finish. Bigger chips also require more

power, which could result in overloading the motor.

Under extreme force-feeding conditions, the relative speed

of the cutter can become so slow—and the bites it has to

take so large—that chips will be partially knocked off rather

than fully cut off. This will result in splintering and gouging

of the workpiece.

PROPER RATE OF FEED

Professional trimming and edge shaping depend upon care-

ful set-up and selecting the proper rate of feed.

The proper rate of feed is dependent upon:

n the hardness and moisture content of the workpiece

n the depth of cut

n the cutting diameter of the cutter.

When cutting shallow grooves in soft woods such as pine, a

faster rate of feed can be used. When making cuts in hard-

woods such as oak, a slower rate of feed will be required.

Several factors will help you select the proper rate of feed.

n Choose a rate that does not slow down the trimmer

motor.

n �Choose the rate at which the cutter advances firmly and

surely to produce a continuous spiral of uniform chips or

a smooth trim edge on laminate.

n Listen to the sound of the trimmer motor. A high-pitched

sound means you are feeding too slowly. A strained,

lower-pitched sound signals force-feeding.

n �Check the progress of each cut. Too-slow feeding can

cause the trimmer to take off in a wrong direction from

the intended line of cut. Force-feeding increases the strain

of holding the tool and results in loss of speed.

n Notice the chips being produced as you cut. If the trim-

mer is fed too slowly, it will scorch or burn the wood. If

the trimmer is fed too fast, it will take large chips out of

the wood and leave gouge marks.

Always test a cut on a scrap piece of the workpiece wood

or laminate before you begin. Always grasp and hold the

trimmer firmly with both hands when trimming.

If you are making a small-diameter, shallow groove in soft, dry

wood, the proper feed rate may be determined by the speed

at which you can travel the trimmer along the guide line. If

the cutter is a large one, the cut is deep or the workpiece

is hard to cut, the proper feed may be a very slow one. A

cross-grain cut may require a slower pace than an identical

with-grain cut in the same workpiece.

There is no fixed rule. Proper rate of feed is learned through

practice and use.

FORCE FEEDING

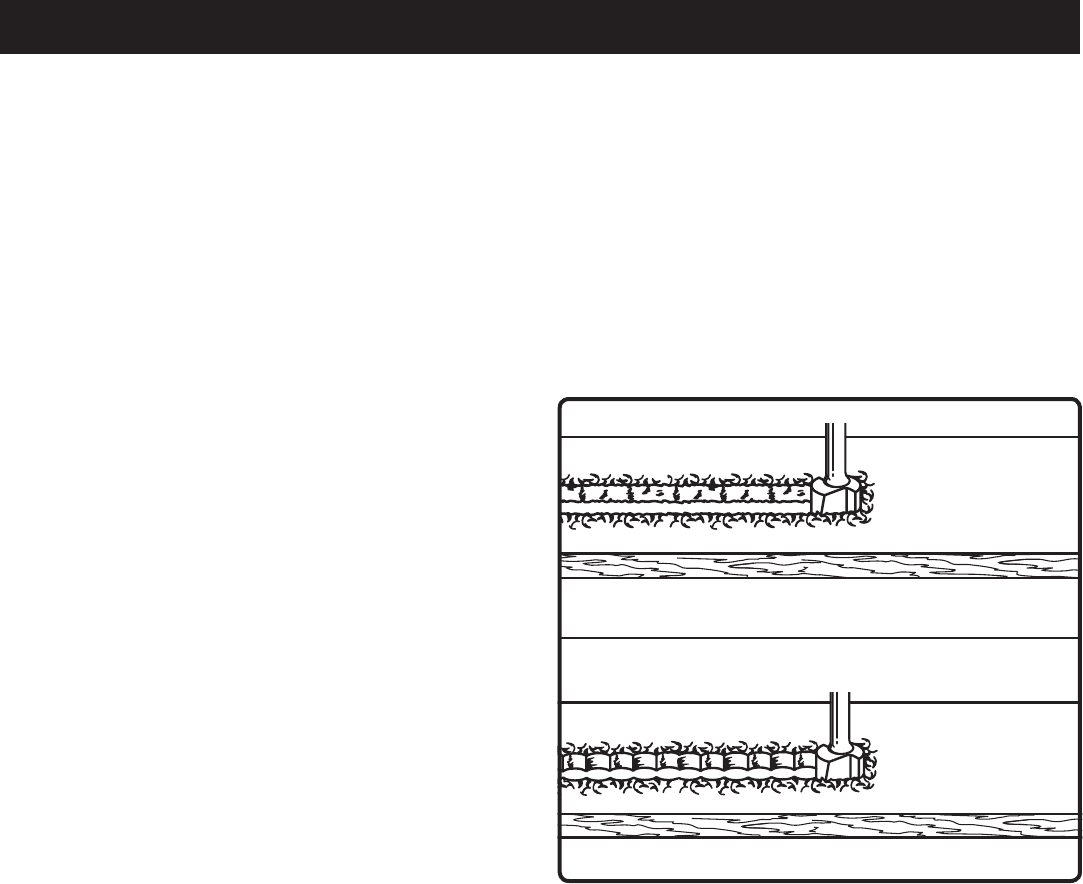

See Figure 8.

The trimmer is an extremely high-speed tool (25,000/min),

and will make clean, smooth cuts if allowed to run freely

without the overload of a forced feed. Three things that cause

force feeding are cutter size, depth of cut, and workpiece

characteristics. The larger the cutter or the deeper the cut,

the more slowly the trimmer should be moved forward. If the

wood is very hard, knotty, gummy or damp, the operation

must be slowed still more.

Clean, smooth laminate trimming and edge shaping can be

done only when the cutter is revolving at a relatively high

TOO SLOW

TOO FAST

Fig. 8

TOO SLOW FEEDING

See Figure 8.

When the trimmer is advanced into the work too slowly, the

revolving cutter does not dig into new wood fast enough to

take a bite; instead, it scrapes away sawdust-like particles.

Scraping produces heat, which can glaze, burn, or mar the

cut, and can overheat the cutter. Dull cutters can also con-

tribute to scraping and burning.

It is more difficult to control a trimmer when the cutter is

scraping instead of cutting. With practically no load on the

motor, the cutter will be revolving near top RPM, and will have

a greater than normal tendency to bounce off the sides of

the cut, especially if the wood has a pronounced grain with

hard and soft areas. The cut that results may have rippled

sides instead of straight.